[ad_1]

Globally, the most significant geopolitical event of 2022 was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the Ukraine war is more than just a geopolitical clash. It has also dealt a heavy blow to globalization. As the energy and grain markets are in turmoil, the old paradox first pointed out by John Maynard Keynes is back. In 1914, the world economy was more integrated than ever before, but the outbreak of World War II severely undermined decades of international economic integration. Keynes suggested that economic globalization and large-scale warfare are incompatible. In our time, too, globalization progressed rapidly as long as the war was limited to Iraq and Afghanistan. But when Russia brought war to the heart of Europe, the logic of security triumphed over economic logic. The theory that trade creates peace by creating interdependence is once again undermined.

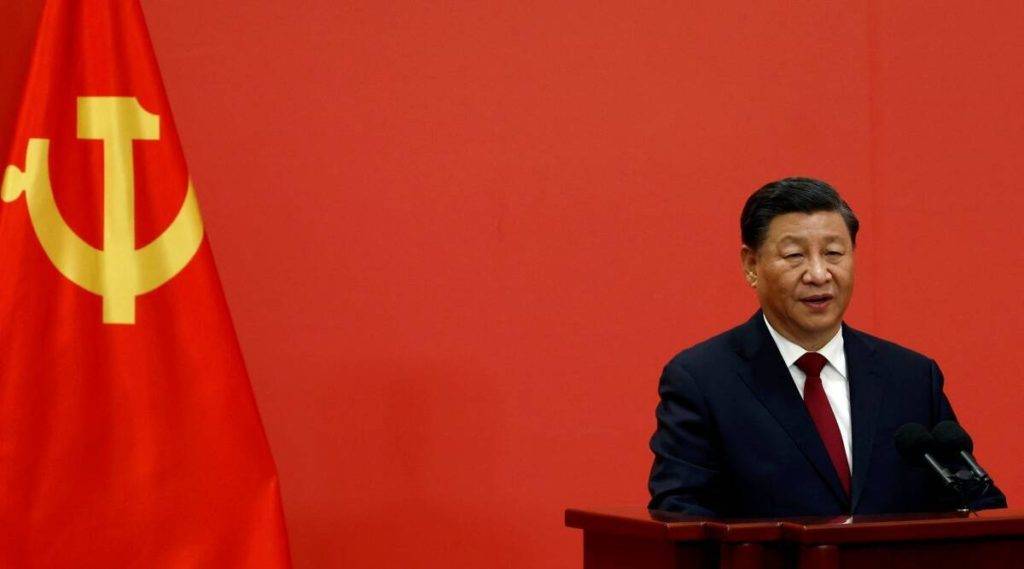

On potentially the same theme, the second most significant development of 2022 was the re-coronation of Xi Jinping for a third term as President of the People’s Republic of China. This appointment broke his two interrelated norms of post-Mao China. Collective responsibility (as in Maoist times he replaced the idea of centralizing power in one leader) and term limits for party leaders and heads of state. For Xi Jinping, no one denies further, even lifelong extensions of power.

This is important for two reasons. Unlike Russia, the world’s 11th largest economy as of December 2021, whose role in the international economy is primarily limited to energy markets, China is the world’s second largest economy and market. It is the largest foreign trader and one of the largest recipients of foreign investment. China’s ability to wreak havoc on the international economy goes beyond natural gas, oil, and food grains if security and economic conflicts erupt.

Second, Xi Jinping’s, in fact Chinese, Taiwan allegations loosely mirror Putin’s allegations about Ukraine. In other words, Taiwan has historically been an integral part of China, so there is no reason to maintain an independent and independent existence. will be immeasurably large. Apart from purely strategic issues, such as whether the United States or Japan will be involved in Taiwan’s defense, some serious economic implications are at stake.

Unlike Ukraine, Taiwan is a developed country. As of December 2021, her per capita income in Ukraine was just under her $5,000 and Taiwan was above her $35,000. Ukraine’s GDP was about $200 billion, Taiwan’s more than hers $820 billion, which included cutting-edge industries such as semiconductors. In addition to this, a comparison between Russia and China. Russia’s GDP is $1.5 trillion, while China’s December 2021 GDP is $17.7 trillion, one-fifth of her $96.5 trillion global GDP estimated by the World Bank. Weak. By Xi’s calculations, if China’s security or power needs necessitated an invasion of Taiwan, the economic impact would be astronomical.

Understanding which direction China is headed under Xi Jinping is therefore not only a domestic Chinese issue, but also an important global issue. More precisely, is President Xi prioritizing the economy over security?

A growing number of Chinese experts believe it is the latter. In the latest issue of International Security (Fall 2022), her three Chinese scholars: Margaret Pearson (Maryland), Megris Meir (Harvard Business School) and Kelly Tsai (Hong Kong) tackle the issue head-on. The fact that a leading security magazine has published an article on China’s economic model should show how security and economics are intertwined under Xi.

Pearson, Lismail, and Tsai argue that Mr. Xi’s economic system is best described as “party state capitalism” to distinguish it from “state capitalism.” The latter basically means that the private sector cannot challenge the dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), even in increasingly market-dependent economies. In 1999, Yasheng Huang (MIT) argued that corporate political priorities in China were becoming clearer. State-owned enterprises were at the top, foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) were next in importance, and private local enterprises, which he called “Chinese enterprises” (ECEs), were at the bottom of the government hierarchy.

The concept of “party-state capitalism” adds something new to this account. It (i) depicts the establishment of the Communist Party’s authority over corporations in a very different way. (2) strengthening the political allegiance of private sector executives, including penalties for those seeking business autonomy; According to Pearson, Rithmire and Tsai, by 2018, 1.88 million non-state enterprises (73% of the total) had established party cells. Xi’s model thus blurs the boundaries between China’s state and corporations. It “obfuscates where the party state ends and the company begins.”

From an outsider’s perspective, this kind of boundary erasure is not a serious problem if it remains confined to small businesses. However, the infiltration of party states in high-tech fields such as 5G communications, semiconductors, robotics, aerospace and marine engineering poses a major security concern, especially for the United States and Japan. Economy and security are not interconnected when party cells are made of textiles and footwear, but when high-tech private enterprise is entwined with the state, they are difficult to untangle.

This was apparently the rationale underlying Biden’s tipping ban on China two months ago, and was supported by both parties. The ban covers not only the sale of cutting-edge chips, but also the sophisticated equipment required to manufacture them, as well as the transfer of strategic knowledge by U.S. citizens or residents. These chips have become integral to the evolution of “future technology” in virtually every field, from pharmaceuticals and artificial intelligence to defense and weapons. Essentially, China would have to produce these chips on its own, which could significantly slow its further industrial progress unless U.S. allies can step in to fill that void.

As India debates its recent border dispute with China, Delhi should keep in mind that China is shifting to a security mode rather than an economic mode, making Chinese compromise less likely. there is. But whether Taiwan, China’s primary security focus, makes the China-India border dispute more or less manageable remains entirely unclear. It could go either way.

The author is Sol Goldman Professor of International Studies and Social Sciences at Brown University.

[ad_2]

Source link