[ad_1]

“It’s very good because the attack stops as soon as the ad disappears, which means it’s not easy to find,” Habiby explains.

The scale was enormous. In June 2022, when the group’s activity peaked, 12 billion ad requests were made per day. According to Human Security, the attack primarily affected iOS devices, but Android phones were also hit. In total, the scam is estimated to have involved 11 million devices. Since legitimate apps and advertising processes were affected, there is little that device owners can do about this attack.

Google spokesperson Michael Aciman said the company has a strict policy against “invalid traffic”, limiting Vastflux’s “exposure” on its network. “Our team thoroughly evaluated the report’s findings and took swift enforcement action,” he said. Apple did not respond to his WIRED request for comment.

Mobile ad fraud can take many forms. As with Vastflux, this can range from ad stacking and phone farms to click farms and SDK spoofing. For cell phone owners, battery draining quickly, data usage increasing significantly, screen turning on randomly, etc. can be signs that the device is affected by fraud. In November 2018, the FBI’s largest fraud investigation led to the indictment of eight men in his two notorious fraud schemes. (Human Security and other tech companies were involved in the investigation.) And in 2020, Uber discovered that the company it hired to get more people to install its app was accused of ad fraud via “click floods.” I won the lawsuit.

In the case of Vastflux, the greatest impact of the attack was on those associated with the sprawling advertising industry itself. The scam affected both advertising companies and apps displaying ads. “They were using different tactics against different groups along their chain of supply and trying to fool all these groups,” said his senior manager of Threat Insights at Human Security. says one Zach Edwards.

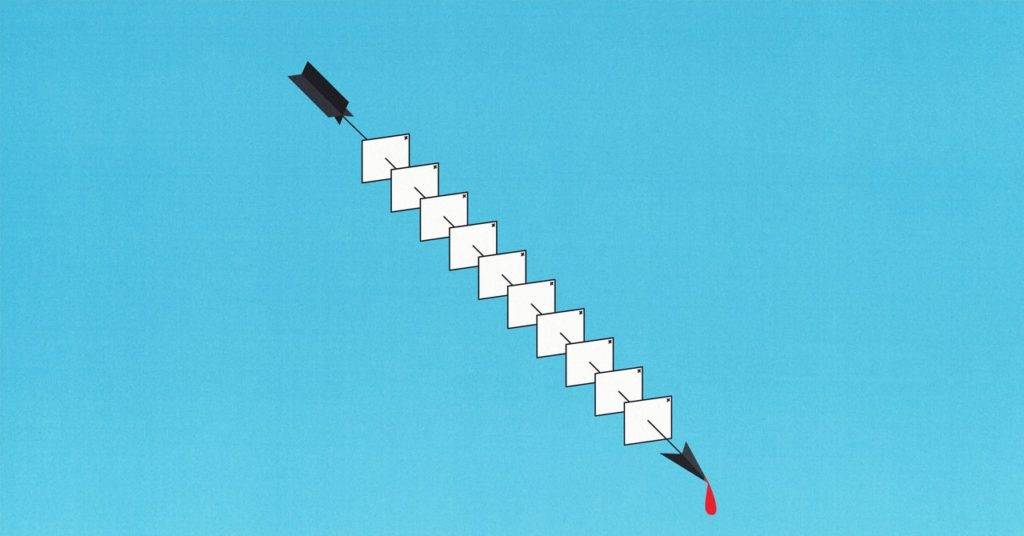

Up to 25 simultaneous ad requests from a single phone are considered suspicious and this group used multiple tactics to avoid detection. They spoofed ad details for 1,700 apps, making it appear that many different apps were involved in displaying the ad, although only one was in use. Vastflux also modified their ads to only allow them to be tagged with certain tags, evading detection.

Matthew Katz, head of marketplace quality at Comcast-owned ad tech company FreeWheel, said threat actors in this space are getting more sophisticated. “Vastflux was a particularly complicated scheme,” he says Katz.

According to researchers, the attack involved several critical infrastructures and plans. Edwards said Vastflux launched attacks using multiple domains. Vastflux is the name of the attack type used by the hacker, which involves linking multiple of his IP addresses to one of his domain names, as well as the video ad template used in the attack. Based on his VAST. (The Interactive Advertising Bureau behind the VAST template did not respond to requests for comment at the time of publication.)

[ad_2]

Source link