[ad_1]

The shooting of rapper Half Oz has sparked popular conversations about gun violence, rap culture, and whether record labels have a responsibility to protect their artists.

The 32-year-old rapper, whose real name is Rataulisha O’Brien, was murdered Monday in the Koreatown neighborhood of Los Angeles. are some of the artists in Her Drakeo the Ruler, who was fatally stabbed in 2021, and Grammy-nominated rapper Nipsey Hussle were also shot dead in Los Angeles in 2019.

Ice-T, the legendary host-turned-actor earlier this year issued a warning To a “young rapper” who was in Los Angeles for a Super Bowl-related gala.

But experts say the problem is much more complicated than that. Elaine Richardson, an Ohio State University professor who specializes in African-American culture, literacy and hip-hop, said it was important to prioritize systemic issues when discussing rapper murders. .

“This reflects the problem of gun violence in the larger society, and the problem of violence in America in general. hmm,” she said.

Gun violence is “part of the condition of black people in society, and everything that is dangerous and harmful to the larger society. There will always be disparities in our communities. It’s part of the way it’s structured,” Richardson added.

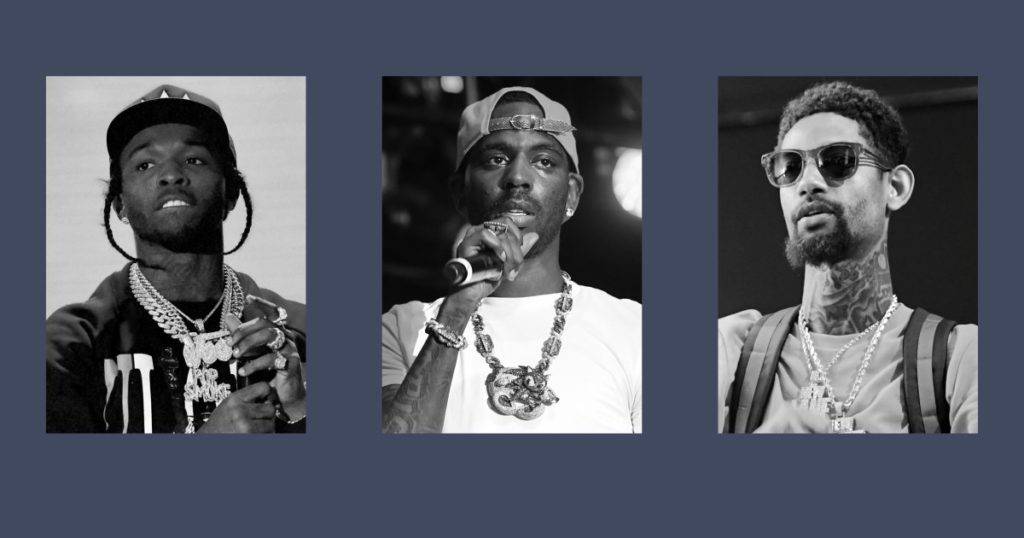

In the aftermath of murders like these, questions often swirl about corporate liability. In particular, record labels pressurize artists to assume “tough guy” personas, claiming they fail to protect them from the violence they promote. This is a question that has plagued the hip-hop community since the shooting death of DJ Scott La Rock in 1987. La Roque, who was part of the influential hip-hop group Boogie Down Productions, was shot dead outside his apartment complex in the Bronx that summer.

For PnB Rock, whose real name is Rakim Haseem Allen, fans speculated whether his former record label, Empire, took out a life insurance policy on the rapper. This claim has not been substantiated by NBC News. Empire’s vice president of artists and repertoire (A&R), Bobby Fischer, said the label only worked with him briefly on his hit single “Selfish” in 2016, and has since made significant progress with him. Rappers, including King Fong and Young Dorf, who said Fisher worked with or distributed music through Empire, were shot dead in Atlanta and Memphis, Tennessee, respectively, in recent years. Fisher said neither fans nor label officials were used to such violence, calling the death “traumatic”.

“I think there is an element of compassion in people who sign artists to ensure their safety. made the claim that more should be done to protect

NBC News was unable to confirm the exact relationship between the aforementioned artist and label.

He pointed out that label officials are limited in what they can do to keep artists safe without controlling their private lives. “They are doing shows and they are going to be with their loved ones. We can provide security in the field of work, but artists have their own lives outside of being artists,” he said.

When a rapper’s obituary makes headlines, it tends to follow with sharp criticism of hip-hop. In February, New York City Mayor Eric Adams condemned drill rap after two artists, Jakan McEnry and Tarjay Dobson, better known as Tdott Woo, were shot dead in Brooklyn. has been pulled from Twitter … but still allows music, gun displays and violence,” Adams said. then saidhas pledged to ask social media companies to remove videos featuring drill music from their platforms. Last month, The New York Times confirmed to management and label representatives that Adams had excluded three drill rappers from the city’s Rolling Loud festival for fear of possible violence.

Academics like A.D. Carson, assistant professor of hip-hop and the Global South at the University of Virginia, denigrate rap music, claiming that the genre is used to reinforce stereotypes and myths about black people. In an essay for The Conversation, he wrote that the rapper’s display of hyper-masculinity and violence was meant to show “a kind of credibility,” adding, “Anyone still trying to denigrate rap should be criticized for rap.” It might be better to focus on the causes of the crisis,” he added. Instead of condemning the music that reflects it, it condemns the violence in America.

Chuck Creekmur, CEO of hip-hop-focused media site AllHipHop, echoes a similar sentiment.

“There are a lot of nuances that people don’t always consider when looking at a rapper’s death. I personally believe it shows what’s going on in our community in general,” he said. “There’s a common belief that rap artists have the most dangerous jobs, but I don’t think so.”

[ad_2]

Source link