[ad_1]

The predictable routine of teaching, writing, and contributing to campus life I’ve developed over the past two decades was shattered last fall by the largest strike at a US higher education institution. The readiness for the start of the winter semester throughout the University of California system is a reflection of the disappearance of the fall without a normal closure and of the relationships I have cultivated with my students through years of practiced intentionality. It feels different in 2023 because the senses are frayed.

I’m not a historian with nostalgia for the good old days (which, frankly, were never good, even for the elite), or a seasoned professional who finds comfort in the familiarity of the status quo. . I study change and change makers. I admire the disruptor culture that is part of today’s tech sector. I took to the streets to instigate change in the United States and South Africa. Nevertheless, I miss the civic ideals of the University of California where I grew up. It is a social contract in which taxpayers, governments and students prioritize multifaceted universities as public goods, and university administrators prioritize students and research. Student center and fundraising campaign.

But nostalgia doesn’t help us live in the present. As a world historian, studying the past on a global scale has taught me a few things to help me think about the aftermath of the UC strike.

- Change is hard.

- Systemic change comes with costs that are disproportionately borne across society.

- The elite and those in power are not willing to give up their privileges.

- It is difficult to comprehend the magnitude of change in one lifetime.

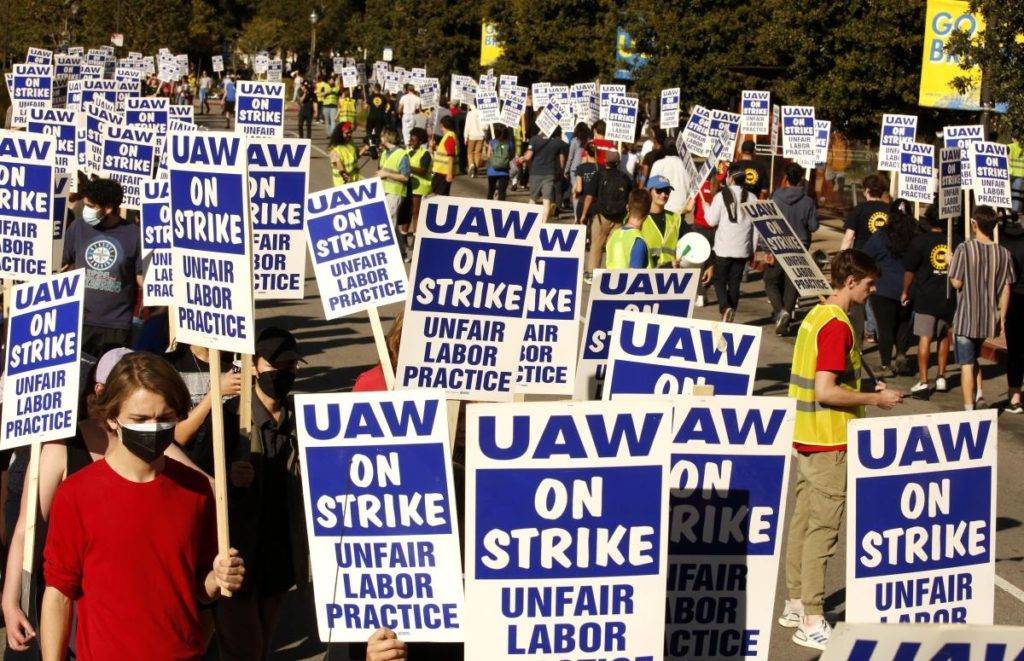

The fact of the strike exposes the cracks in the current higher education structure. The hard work of graduate students, the uncompromising attitude of the university, and the frustration of undergraduates at not being able to get the classes and services they paid for show how deep the rift is. Significant improvements in wages and benefits for teaching assistants, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows are groundbreaking changes and mark an important triumph for organized labor.But the contract was ratified split voteAt the same time, 98% of the votes were in favor of the strike, while about 62% of the teaching assistants and 68% of the postgraduate researchers supported the agreement. The new agreement falls far short of the union’s goals, and many graduate students are wondering if the effort and sacrifice of the strike were worth it. It doesn’t address the underlying problem.

Additionally, the benefits will be phased in over several years. Seasoned negotiators know that winning labor concessions is often long term. Implementing new contracts takes time. Even in the temperate coastal California climate where most of UC’s campuses are located, this is uncomfortable for students who have to pay for heating. Contracts are landmarks, but celebrations are quiet everywhere.

As I celebrate the achievements of my graduates, I mourn their awkward limp through the end of the fall semester. The last day of the class period usually feels like a happy achievement. I share pride with my students. We worked hard together and achieved great things. We also share relief. We’ve worked hard and a well-deserved break is just around the corner. These things were still true in December 2022, but we didn’t get together in a lecture hall that past Friday to reflect, ask new questions, put together a final paper, and brainstorm. End-of-term course evaluations reflect absences in ways I didn’t expect. Undergraduates may complain about the amount of work, but most students really want to learn something. Many who sympathized with the graduate student’s arguments also made their own sense of loss clear. Variations of “It’s not fair” were interspersed in my evaluation of a large lecture course. they are right

During the last three weeks of the semester, I didn’t get to meet my undergraduates in person. There was no final meeting of the faculty (me and her three graduate student teaching assistants) to standardize the final paper grades. During the strike, I respected the picket lines and withheld my labor in solidarity with their collective action.

The university says it values the work of those who do much of the front-line teaching and day-to-day work in our lab.Faculty says they see graduate students as early-career colleagues . But the university structure and financial support for graduate students tell a different story.

Yes, they are students engaged in coursework and supervised research towards an advanced degree. They are also skilled and talented adults who are financially independent. They should be able to live safely and pay rent to feed themselves without official assistance.

Earning a postgraduate degree is a professional choice, much like getting a job as a management trainee in a large company, but without the benefits of a high salary in the future. Few faculty went to graduate school expecting to get rich, but most of us expect to be able to pay the bills and keep a roof over our heads. Or 30 years ago.

Today’s graduate students live in today’s economy. We need a different system than the patchwork of annual scholarships, short-term research gigs, boring summer jobs, and temporary jobs that sustained me and my cohorts in the 1990s. Sure, we survived it (most of us, anyway), but it’s a better bet for the current generation facing more extreme financial, emotional, and health strains. That doesn’t mean it can’t be done. The new agreement will increase scholarships, which is welcome, but won’t change the university’s reliance on low-wage workers to get the job done. .

I was one of the UC graduate students who went on strike for union rights in the mid-1990s. Our goal has been to create workplace equity since his first TA contract in 2000. This cohort of student workers asked for more. Universities should listen. It’s not just about wage increases. The strike is over, but uncertainty and deep inequalities remain.

We all need to be mindful of the raw emotions everyone is going through and get back on campus in the new year. Split voting also divides relationships and political solidarity. Undergraduates wonder if faculty and teaching-her assistants care about the impact on them, making the imbalanced power relationship even more troubling. A faculty member who relied on the efforts of her teaching assistants to help students prepare and mark their final exams is working on student assignments that have not yet been graded. Meanwhile, the registrar’s office awaits final grades (as do undergraduates wondering where they fit in this complex equation). Those same faculty are also busy preparing for the last quarter of a brand new set of classes.

If you want to continue to attract ambitious, talented, and diverse scholars, willing to defer full-time wages and years of savings for retirement, graduate school is the professional choice. It should be remembered that it is not a required professional mission. vow of poverty. It is also good to bear in mind that the process of education, especially the most rigorous, is best approached in the spirit of nurturing rather than extraction.

I am deeply saddened to learn that I will never see most of the 180 undergraduates who accompanied me on the path of ancient world history last fall. I hope that in his failed seven weeks with us, they will learn analytical skills and enough history to make their own decisions about the costs of this strike and the benefits to society of a robust system of higher education. increase. If universities really take their mission seriously, their leaders will start thinking about what sustainable structural change looks like. Because even a wage-focused patch to a broken system would strain resources without addressing the underlying problem that higher education jobs are predicated on low wages. Its most vulnerable employee.

[ad_2]

Source link