[ad_1]

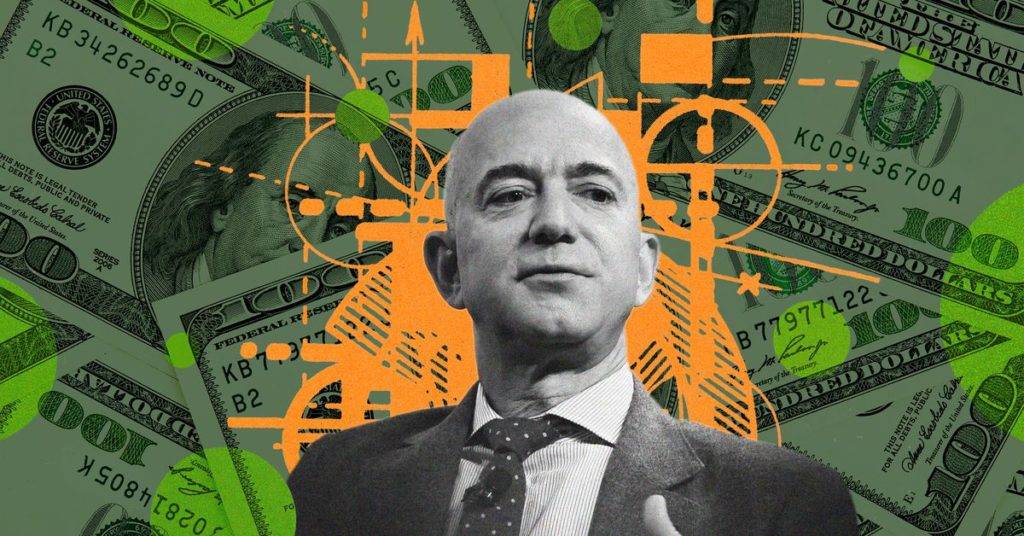

During a CNN interview last fall, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos revealed that he intends to give away most of his fortune — $120 billion as of January 2023.

When one of the richest people in the world signals that his immense wealth will go to helping others, ears tend to perk up. The announcement brings into focus how the business tycoon will spend the coming years, but it also raises plenty of questions around the way he plans to dispense such an unfathomable sum of money. Who will Bezos give his wealth away to, and how quickly? How will the world be affected?

We know this much: He’s given country singer and philanthropist Dolly Parton $100 million to spend as she wished, but beyond that, Bezos hasn’t yet shared much detail. He’s issued no press release sketching out an overarching vision for where his hundred billion-plus dollars — an amount bigger than some nations’ GDPs — will go. Bezos also hasn’t signed the Giving Pledge, a commitment started by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett in 2010 that calls on the world’s wealthiest people to pledge at least half of their wealth to philanthropy. Famous signatories include Bezos’s own ex-wife MacKenzie Scott, Michael Bloomberg, Elon Musk, George Lucas, Mark Zuckerberg, and even fallen crypto king Sam Bankman-Fried, whose name has been removed from the site. Pledges often come with a letter that elucidates what inspired the commitment and what their philanthropic priorities are. In her letter, for example, Scott expressed why she doesn’t believe in waiting to give her “disproportionate amount of money” away. “I will keep at it until the safe is empty,” she wrote. By comparison, Bezos has been fairly reticent to discuss what motivates his philanthropy and the pace at which he’ll do it.

Unlike philanthropists such as Bill and Melinda Gates, who have specialized in global health funding for decades, Bezos has so far given hefty grants in disparate areas, such as homelessness and climate. “It feels a bit piecemeal,” said Rhodri Davies, founder of Why Philanthropy Matters, a site that publishes analysis and commentary on the philanthropy world.

“[Bezos] kind of has a habit of rushing with these big announcements, and then not having a lot of detail to answer some of those follow-up questions,” said Davies.

Some of the curiosity around Bezos’s new philanthropic streak stems from the fact that Amazon, the source of his fortune, is increasingly under scrutiny. Amid the pandemic, Amazon raked in incredible profits as online shopping demand soared — and faced a torrent of negative press, from allegations of pandemic price gouging to the long-simmering labor issues that erupted in 2020 through worker protests and culminated in the recognition of the first Amazon union in the US last spring. Last year, tech companies’ stocks cratered from their pandemic surge, but that did little to threaten Amazon’s standing as one of 2022’s most profitable American companies. The growing size and reach of the “everything store,” however, has affected its public perception: A 2019 CNBC survey of 10,000 Americans showed that a majority of respondents believed the company was bad for small businesses.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24373778/GettyImages_1421123241a.jpg)

Bezos is no longer Amazon’s CEO, but as the company’s biggest individual shareholder, his money remains tied to Amazon’s fortunes, and his sudden commitment to saving the world is being met with criticism from some in philanthropy and activist circles who argue that his philanthropic vision is disjointed and fails to be bolder, especially considering Amazon’s record on labor and climate. But Bezos’s giving is also impressing others with the no-fuss simplicity of his grant-making style and his trust in respected experts.

Bezos’s philanthropic track record

Before 2018, Bezos didn’t have much of a philanthropic résumé. It was a source of growing criticism from the press and nonprofit experts as his net worth climbed, topping $100 billion by the end of 2017. He’s since kicked his philanthropic efforts into high gear, committing $2 billion to his Day 1 Families Fund in 2018, of which about $521.6 million so far has been granted to organizations addressing homelessness, and in 2020, announcing the $10 billion Bezos Earth Fund (BEF). In an Instagram post announcing the fund, Bezos wrote, “Climate change is the biggest threat to our planet. I want to work alongside others both to amplify known ways and to explore new ways of fighting the devastating impact of climate change on this planet we all share,” noting that averting the crisis would require action from “big companies, small companies, nation states, global organizations, and individuals.”

Since stepping down as Amazon CEO in 2021, Bezos has had more time to focus on this new chapter of his public life. With the Bezos Earth Fund, which responds to the climate crisis with an emphasis on conservation and restoration, he indicated that he would give away roughly $1 billion a year through 2030. According to the fund’s website, it has granted $1.63 billion since its launch.

That’s both a lot of money for the relatively small number of nonprofits receiving lump sums of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars — and not a lot of money, given that Bezos is worth north of $100 billion.

What’s been most notable about Bezos’s approach so far is how surprisingly easy it is for organizations to receive grants from him. Applying for a grant can often be a long, burdensome process for nonprofits. With the Day 1 Families Fund, Bezos has appointed an advisory board that reaches out to organizations to recommend that they apply for a grant, removing a lot of the leg work and uncertainty from grant seekers. PATH, a homelessness prevention organization based in Los Angeles, received $5 million from the Day 1 Families Fund this past November. Tyler Renner, PATH’s director of media, recalled that the application was “simple and straightforward,” amounting to about 2,000 words. PATH has flexibility in how to use the funds — but the fund stipulated that it had to focus on “ending homelessness for families.”

“The grants have few restrictions and often grantees note this as an important benefit to doing what is needed most,” a spokesperson for the Day 1 Families Fund confirmed to Vox.

Solo Por Hoy, Inc, a nonprofit based in San Juan, Puerto Rico, providing assistance with homelessness and other crises, received an email out of the blue in August from the Day 1 fund saying that the advisory board had recommended it for a $600,000 grant. “Prior to that I had never heard of this foundation before,” Belinda Hill, Solo Por Hoy’s executive director, told Vox in an email. Then, at the end of October, the organization was told that, in fact, it would be granted $1 million. “I can tell you it is a game changer for us and the homeless population we serve,” said Hill.

LA Family Housing, one of the largest homeless services providers in the Los Angeles region, received a second $5 million grant from the fund last year, with the first having come in 2018. The only restriction, again, was that the money be used to support families experiencing homelessness, rather than individuals. Stephanie Klasky-Gamer, the group’s president and CEO, echoed that the process was remarkably streamlined. “We received a call, and then an email inviting us to apply,” she told Vox. The application itself was just one or two prompts. “The prompt was something like, ‘You find yourself at the intersection of needing an emergency response to accomplish long-term sustainability on ending family homelessness — please propose what you would do.’”

“I thought it was thoughtful and respectful of the expertise,” she said.

Safe choices?

One of the emerging criticisms of Bezos’s philanthropy is that in striving not to be controversial, it misses funding approaches that attack the deeper roots of the climate crisis and homelessness that advocates say need urgent attention.

Marion Gee, co-executive director of the Climate Justice Alliance (CJA), told Vox that many of the initial rounds of Bezos Earth Fund grants went to “much bigger, Big Green organizations that often fund market schemes [and] techno fixes.” It gave a whopping $100 million each to already well-funded organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund and the World Wildlife Fund that, in the Alliance’s view, don’t disrupt the status quo of fossil fuel dependence. Focusing on environmental conservation is also less politically heated than organizations that frame the climate crisis as a problem of unfettered capitalism, of economic extraction and injustice, that harms communities of color most.

The CJA has not received a grant from the BEF, but it has been in conversations with the organization about where its grants could go. “From a climate justice perspective,” Gee said, “we pushed back hard and asked those groups [that did receive grants] to reallocate some of that money directly to the Fund for Frontline Power,” which gives money to communities that have been directly and disproportionately impacted by environmental injustice.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24373821/GettyImages_1242727828a.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24373822/GettyImages_1242727664a.jpg)

The Bezos Earth Fund has shown some willingness to listen. In 2021, seemingly in response to activist pressure, it granted about $150 million to at least 19 different climate justice organizations in support of the Biden administration’s Justice40 initiative. It gave $4 million to the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, which conducts research and policy advocacy in the Gulf Coast, including the Mississippi River Chemical Corridor — also known as “Cancer Alley” — where a proliferation of petrochemical factories has increased the risk of cancer in the predominantly Black neighborhoods where many plants were built. The BEF also gave $6 million to WE ACT, a group that works to ensure low-income communities of color have a voice in shaping environmental health policies, as well as $5 million to climate justice group Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) to build more climate-resilient infrastructure in California.

Andrew Steer, president and CEO of the Bezos Earth Fund, told Vox in a statement that it was led by a team of diverse experts in climate science, philanthropy, public policy, and other fields. He did not respond to questions from Vox asking for further details on how its grant-making process worked — such as whether it used an advisory board that makes recommendations the way the Day 1 fund does. “We remain committed to environmental justice, granting over $300 million so far to environmental justice groups in the US,” wrote Steer.

Climate justice advocates have balked over some of these grants. Late last year the BEF, in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation and the State Department, announced the creation of a carbon offset program called the Energy Transition Accelerator. It would allow corporations in wealthy countries to buy offsets for their carbon emissions, and that money would go to renewable energy projects in developing countries. But carbon offsets have a dubious track record; it’s hard to ensure that emissions have actually been offset. The BEF has also dedicated $11 million to initiatives focused on improving the quality of voluntary carbon markets.

In an email to Vox, Gee called these latest BEF grants “very wide of the mark.” “These grants do not cut emissions at source, allow for continued pollution of frontline communities, prolong our dependence on fossil fuels, and divert needed resources from real solutions grounded in justice, equity, and sustainability that work for people and the planet,” she wrote.

Similarly, though the Day 1 Families Fund has doled out grants to well-respected organizations providing crucial homelessness services, critics say it has mostly focused on groups addressing family homelessness, which is more likely to be temporary, while neglecting chronic homelessness.

“The people experiencing chronic homelessness are so enormously neglected in philanthropic giving,” Sara Rankin, a law professor at Seattle University and director of the law school’s Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, told Vox.

“You’re never going to find me or anyone else saying that family homelessness is not worthwhile or important to pay attention to,” she said. “But what I’m saying is, the history of philanthropic giving, especially when you focus on homelessness, completely excludes the most visible, arguably the most vulnerable, and the most costly segment of the homeless population — which are people experiencing chronic homelessness.”

This is especially worrying because around 30 percent of homelessness is chronic, and that number is increasing. It often occurs because the person has a disabling condition that prevents them from working and maintaining housing. People who are chronically homeless aren’t usually families, but single adults, and they’re more likely to face violent forced hospitalization, criminalization, and public contempt. It’s politicized in a way that family homelessness is not — and less palatable for philanthropic giving, which has historically been “overwhelmingly focused on really sympathetic recipients, like families, children,” said Rankin. “You get a double bang for your buck by donating to sympathetic recipients — it sort of fulfills a marketing function as well.”

The failure to be bolder for fear of reputational damage is a problem of philanthropy in general, and not just Bezos. But it underscores the limits of philanthropy in effectively, radically solving problems, especially when billionaire donors place limits and stipulations on grants. The virtues of no-strings-attached, trust-based philanthropy — in which donors rely on grant recipients to know best how their grant should be used — have become widely discussed in the sector in recent years, but it’s still fairly uncommon for billionaire philanthropists to bestow unrestricted gifts. (Scott is one notable exception, having become renowned in the few years since signing the Giving Pledge for giving enormous gifts to smaller grassroots organizations, with no strings attached.)

Rankin mused that a number of people on the Day 1 fund’s advisory board, which she praised as being full of “incredibly smart and experienced professionals in the homelessness space,” would likely agree that the fund needs more focus on housing solutions and chronic homelessness. “But they don’t get to determine the philanthropic mission,” she said.

Bezos the philanthropist enters the spotlight

Philanthropists craft their image not only through the kinds of organizations they fund — and which they exclude — but also through showy announcements and events where they’re lauded for their work. In October of last year, Bezos received an award that conferred philanthropic prestige from a venerated moral authority: the Vatican. One of the recipients of the inaugural Prophets of Philanthropy Award from the Galileo Foundation, a tax-exempt nonprofit supporting the initiatives of the Pope, Bezos gave a speech at the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He also made a $200 million donation to the Smithsonian last year — the largest since its founding — that comes with 50-year naming rights to a new building within the institution.

Linsey McGoey, a professor of sociology at the University of Essex and author of No Such Thing As A Free Gift, said that billionaire philanthropists often make announcements “in a way that’s geared at high-press visibility.”

“There’s no doubt, with the resources at his disposal, it’s incredibly important to pay [Bezos] attention,” said Ben Soskis, a senior research associate in the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy at the Urban Institute. “But he clearly also wants a certain kind of attention.”

Soskis described Parton receiving the Courage and Civility Award from Bezos as “heavily choreographed.” “Bezos himself was an important part of that ceremony,” he said, and the award cemented his association with a largely beloved celebrity. The award went to Parton personally, not to her Dollywood Foundation, and the singer has not yet revealed how she plans on using the $100 million.

In past years, Bezos gave the award to other well-known figures, such as CNN political commentator Van Jones and chef José Andrés. He has also invited several celebrities on space flights with his aerospace company, Blue Origin, including actors Pete Davidson (who later backed out) and William Shatner, and Good Morning America anchor Michael Strahan.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24373839/GettyImages_1346422416a.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24373858/GettyImages_1329731718a.jpg)

“I think there’s often an element of philanthropy that is driven a bit by a desire for recognition and social status,” said Davies.

Compared to philanthropists like ex-wife Scott, Bezos has yet to find his distinct identity, experts said.

If Bezos does have a philanthropic identity, said Soskis, “it probably has more to do with his identity as an entrepreneur — the entrepreneur as someone who transcended politics, which is itself very much a political stance.”

That’s become evident in the vague manner in which Bezos has spoken publicly about his philanthropic values. During his CNN interview, explaining why he chose Parton to steward his $100 million gift, he emphasized that she behaved “always with civility and kindness.” He lamented that the world was full of conflict and “ad hominem attacks,” but gave no specific examples of the kinds of political divisiveness he referred to.

“We want to bring a little bit of light, a little bit of amplification to these people who use unity instead of conflict,” he continued.

Amazon looms over Bezos’s generosity

Despite Bezos’s efforts to keep his philanthropic giving apolitical, the manifold criticisms of Amazon’s business model, much of which was formed during his 27 years as the company’s chief executive, have become impossible to ignore: There are the labor concerns that have only grown as the company has strived for e-commerce dominance, accusations of tax avoidance, its rising carbon emissions. Amazon has complicated how Bezos’s generosity is digested in the public eye. His money goes to good causes more often than not, but how does the impact of Bezos’s philanthropy weigh against the record of the company where he continues to make his wealth?

It’s a question that’s become more urgent for modern-day philanthropists. Once upon a time, it was more common for the wealthy to wait until the twilight of their lives to bestow their fortunes (and names) to universities, museums, and other cultural institutions. The old model exemplified by Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller was “you make your money, people hate you, and then you start giving it away and people like you in the last decade,” said Soskis. Today, there’s more public pressure against the waiting approach, as Bezos experienced before starting the Day 1 fund in 2018. There are also a lot more billionaires today (north of 2,600 by Forbes’s count) than there were during the Gilded Age. “The problem of publicity is increasingly more prominent in the time when you have engaged living donors, especially if they are making the money at the same time they’re giving it away,” Soskis said.

It makes the relationship between who they are as philanthropists and who they are as business magnates more visible — negative press around a billionaire-owned company can break alongside an announcement of a giant philanthropic gift. The week that Bezos announced that he plans to give most of his wealth away, news of impending mass layoffs at Amazon broke, and in early January the company revealed that close to 18,000 employees would lose their jobs.

“I think whenever Jeff Bezos comes out and says, ‘I’m doing something philanthropic,’ 80 percent of the coverage, if not 90 percent, is yes, but what about the way you treat work in warehouses and pay taxes?” said Davies.

Those are far from the only issues complicating the reception to Bezos’s personal philanthropy. The impact that corporations like Amazon can have on gentrifying already high-cost areas has become a hot-button issue too, standing at odds with the work that the Day 1 Families Fund is doing. Amazon’s announcement in 2017 that it would construct a second headquarters outside of Seattle sparked a furious bidding war between cities — and equally furious opposition from residents and politicians. In its hometown, when Bezos was still Amazon CEO, the company also gained notoriety for helping snuff out a bill that would have levied an extra tax on Seattle’s big businesses, aiming to raise an extra $47 million per year to address the homelessness and affordable housing crisis in the area. The city council passed the bill in a unanimous vote; Amazon voiced its displeasure by halting construction on a new downtown office. Less than a month after the bill’s passage, it was repealed.

The next year, Amazon spent $1.5 million on the Seattle city council races — a record-breaking amount for its city council elections — in support of a more pro-business council and to defeat council member Kshama Sawant, a stalwart Amazon critic who sought to raise corporate taxes.

Having made its position on taxes clear, in 2021 Amazon launched a $2 billion fund for affordable housing in Seattle and other regions across the US. Its Housing Equity Fund has so far invested $500 million in the form of grants and loans to affordable housing developments, including another recently announced $150 million commitment. Compare that to the $47 million per year Seattle’s city council hoped to raise. But it also sends a message: Amazon is willing to bestow generosity on its own terms, not on the government’s.

Perhaps the biggest elephant in the room is the dissonance between Bezos’s climate philanthropy and Amazon’s ballooning carbon emissions. The company’s emissions, which stem not only from its products but also its corporate offices, data centers, and warehouses, and its increasing growing delivery and logistics services, grew by 18 percent in 2021, and are likely to keep growing as it continues to expand warehouses.

According to Reveal from The Center of Investigative Reporting, this is likely an undercount, because unlike major retailers like Walmart, it doesn’t include emissions from products it sells made by third-party manufacturers. According to a new report from environmental non-profit Oceana, its plastic packaging waste — a major source of ocean pollution — also increased by 18 percent in 2021. The Bezos Earth Fund made a $50 million grant at the UN Ocean Conference to help expand the number of marine protected areas.

It’s a conflict that Gee of the Climate Justice Alliance has grappled with. Should climate activists refuse to associate with or engage with the Bezos Earth Fund given the source of its money? “The wealth accumulation is based on extraction,” said Gee of the Climate Justice Alliance. “We know that this money has come from paying workers low wages and harsh conditions.”

Ultimately, by Gee’s calculus, taking money seems better than leaving it in a billionaire’s hands. “We know, as a climate justice organization, if we don’t try to influence where that money will go, it will continue to go to things that just continue to allow pollution, continue to allow harm to frontline communities,” she said. “It puts us in a difficult position where we’re relying on billionaires that have capitalized on the extractive economy to make the transition that we need.”

The Asian Pacific Environmental Network, which received $5 million from BEF, echoed the sentiment that it was important to proactively try to shift money to climate justice groups. “The amount of money that was going to be pouring into the climate space — it would have a real impact on the conditions that our climate justice movement will face in building power for a just transition,” said Vivian Huang, a co-director at the organization. She noted that the fund’s initial $100 million grants went to “large traditional environmental organizations” advocating for policies “that allow big polluters to continue treating our neighborhoods as environmental sacrifice zones.”

Amazon was also a major presence in APEN’s internal conversations around whether to apply for a BEF grant. “While most of the funds distributed through philanthropic foundations are gained through the exploitation of land and people, the scale and immediacy of the impact that Amazon has had on our communities has been devastating,” Huang said. “From inhumane working conditions to tax avoidance and increasing pollution burden, Jeff Bezos is remaking entire industries to concentrate even more profits in the hands of the wealthy at the expense of workers and communities.” APEN and the Bezos Earth Fund agreed that if the group applied for a grant and received one, it would still be able to join and support future campaigns around Amazon’s labor and climate issues.

Ultimately, Bezos’s philanthropy won’t fix the harms caused by Amazon. “If he wanted to redress those harms, he could change the practices of his company, recognize Amazon worker unions, and negotiate fair contracts,” said Christine Cordero, co-director of APEN. Cordero noted that billionaires should be giving their wealth away, but that there were still a lot of concerns around how philanthropic decisions are made and by whom.

This past March, a youth-led feminist organization called FRIDA made waves when it revealed it had received a $10 million gift from Scott, whose billions also come from Amazon stock — and made clear that it considered the money a kind of reparations. “While we are humbled and excited to receive this donation and map out the ways in which this money could strengthen the FRIDA community and our existing strategy, we acknowledge the source of MacKenzie Scott’s wealth and its association with one of the most exploitative companies in the world,” the announcement post read. “We work to challenge wealth and privilege, and recognize that philanthropic giving exists because of inequality and exploitation.”

Philanthropy also can be an attempt to erase negative reputations. Today, Bill Gates is synonymous with global health philanthropy; the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has an estimated endowment of $70 billion, and it’s the second biggest contributor to the World Health Organization. But Gates’s entry into philanthropy roughly coincided with a tumultuous time at Microsoft in the late ’90s, when the tech giant was facing a major court case accusing it of ruthless, anti-competitive practices. Today, that controversial past has mostly been smoothed over, and Gates is first and foremost associated with the image of a benevolent, thoughtful public citizen.

In the wake of the scandal surrounding Sam Bankman-Fried and his crypto exchange FTX, the concept of “earning to give” was suddenly everywhere. Bankman-Fried’s version of effective altruism argued that one should maximize their wealth because that would also maximize the amount of money one could give away. But a certain variation of this logic exists in philanthropy at large. Philanthropists have long leaned on their ability to do a lot of good for society as a justification for deeply unequal wealth distribution. If, in the end, their riches were benefiting the public — wasn’t that wealth well-earned?

The “burden” of giving money — and control — away

Bezos’s fairly muted announcement may or may not pan out. The fruits of it also probably won’t be seen right away.

In his November CNN interview, Bezos called philanthropy hard. “There are a bunch of ways you can do ineffective things, too,” he remarked. It’s a surprisingly common sentiment among the ultra-rich. Elon Musk echoed this sentiment not long ago, saying, “If you care about the reality of doing good and not the perception of doing good, then it is very hard to give away money effectively.”

There’s some truth to it, but it’s also a line big donors have long used to justify taking their time. The narrative dates back to the days of Carnegie and Rockefeller, said Soskis. In one way, it served to “legitimize the vast accumulation of wealth” by presenting philanthropy as a great burden to shoulder. “Heavy weighed the crown for the industrialist,” he said. It painted an image of a “careworn philanthropist, who was so focused on giving away money well.”

“At that time as well, there was this focus on the distinction between indiscriminate giving and scientific philanthropy, which was discriminating and focused and really paid attention to outcomes,” said Soskis.

But there’s no dearth of experts and activists willing to put forward thoughtful, effective ideas on how wealth can be redistributed, and there’s a huge gap in funding for the climate crisis in particular, which only received about 2 percent of philanthropic dollars as of a 2020 report. Gee pointed to the many climate justice groups — as well as intermediary funds that exist to figure out which grassroots groups need money — that are prepared to receive and spend grants today. “There are mechanisms, there are projects, there are solutions that are already being implemented,” she said.

In some ways, the billionaire philanthropist’s pledge to give away their fortune is an acknowledgment that they have far more than they could ever spend on themselves, and that their wealth continues to accumulate at an astonishing clip. If Amazon’s value increases, Bezos stands to passively add to his already enormous pile. Part of why Scott is uncommonly well-regarded even among critics of billionaire philanthropy is her super-charged pace of giving. Since divorcing Bezos in 2019, she has donated at least $14 billion. In contrast, Bezos, who has much more money than Scott’s $28 billion, has given away about $2.4 billion, according to Forbes. That’s about 2 percent of his wealth.

Whether or not one agrees with Scott’s rapid-fire approach, it’s a counter-argument to the claim that giving billions away is so difficult that it takes decades, if not entire lifetimes. She’s become the role model of a less prescriptive model of philanthropy that hands off decision-making power to the people receiving grants — often grassroots groups and schools — instead of the wealthy philanthropist writing the checks. But committing to this strategy requires ceding control.

For Davies, it’s one of the biggest questions he has about the Amazon founder’s future as a philanthropist: Will Bezos be willing to give away not just money, but power as well?

[ad_2]

Source link