[ad_1]

Journalist Jonathan Abrams spent the last four years compiling an enlightening, entertaining, and deeply researched history of hip-hop. Abrams traces the music’s humble beginning in the Bronx and DIY block parties to some of the most popular music in the world today. In this exclusive excerpt from “The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop,” Abrams tells how the infamous 1977 New York City blackout helped electrify a sound and cultural force.

LEMONADE FROM LEMONS

Bronx, New York, 1973–1979

Clive Campbell migrated as a child with his family from Jamaica to the United States in the late 1960s, leaving one country roiled by political instability for another. In Kingston, Campbell had become infatuated with the reggae and dub music that blared from giant portable sound systems, and DJs who toasted or talked over instrumental tracks. Campbell arrived in the Bronx during the reign of feel-good disco music, which intersected with the civil rights era and the dire financial straits of a New York City that was facing a declining population and labor unrest. Campbell involved himself in the city’s emerging graffiti scene — which had arrived after originating in Philadelphia — and assumed the tag name Kool Herc.

On August 11, 1973, Campbell hosted a back-to-school fundraising party for his sister, Cindy, at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the west Bronx — and he is widely credited with birthing hip-hop on that day. By then, the teenage Campbell had assembled his own massive sound system, along with an eclectic record collection that included selections from James Brown and the Incredible Bongo Band. At the party, before an appreciative audience of neighborhood teenagers, DJ Kool Herc performed his “Merry-Go-Round” technique of isolating and prolonging the breakbeat sections of songs (the drum patterns used in interludes — breaks — between sections of melody) by switching between two record players.

DJ Kool Herc became a folk hero in the Bronx as his parties attracted larger and larger crowds. He hosted popular block parties and created Kool Herc & the Herculoids with Clark Kent. Acrobatic dancers known as B-boys, B-girls, and breakers (the media eventually labeled them as break dancers, a term still in wide circulation today) flocked to DJ Kool Herc’s parties to compete in dance circles — no longer having to wait out lengthy songs for a brief moment to get down. DJ Kool Herc enlisted the help of his friend Coke La Rock, regarded as hip-hop’s first MC, as La Rock adapted toasting by shouting out the names of friends and encouraging partygoers to dance.

In time, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash joined DJ Kool Herc as Bronx DJs who forged groundbreaking contributions and laid the foundation for hip-hop to flourish, spread, and evolve.

DJ Charlie Chase (Cold Crush Brothers): The Bronx [in the late 1960s and ’70s] was the epicenter for poverty, the epicenter for kids who were full of energy, who didn’t know what to do with it, didn’t have a lot of activities, didn’t have role models.

MC Debbie D (artist): The backdrop to the South Bronx is poverty-stricken — crime, gangs, slumlords, abandoned buildings everywhere. So they had coined the Bronx “The Bronx Is Burning.” And they wasn’t putting money into safe havens for young people. So, with the music outside, you went to a jam; there’s a thousand kids standing there. We ain’t got nothing else to do.

Michael Holman (journalist): A lot of young people are going downtown to see major live acts like [Patti] LaBelle, James Brown, Funkadelic, as well as going to the famous discos, wearing their best clothes, doing the latest dances, and leaving those young punks and all the troubles in the neighborhood behind. What’s left behind is an audience of younger people, teenagers who can do all the dances — hell, sometimes they’re the originators and are the best dancers.

Kurtis Blow (artist, producer): A big part of hip-hop is break dancing, B-boying. The dance was around before hip-hop; the actual dance style was developed from playing soul music and that playlist that [Kool Herc used].

Grandmaster Caz (Cold Crush Brothers): Herc was a mythical figure in the neighborhood. You heard about him before you saw him.

Sadat X (artist, Brand Nubian): I remember Herc being this larger-than-life figure, just muscles, with the glasses on. Herc was the commander, putting people in place.

MC Debbie D (artist): When Kool Herc comes out and he starts playing music, and then other notable DJs get involved — [Afrika] Bambaataa, [Grandmaster] Flash, L Brothers — and they start playing their music, we’re all going to the jams.

Kurtis Blow (artist, producer): He played the music that we wanted to hear. There was a special playlist of B-boy songs, break dance songs — I can rename right now about 10 of them: “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” by James Brown, “Get Into Something” by the Isley Brothers, “Listen to Me” by Baby Huey, “Melting Pot” by Booker T. & the M.G.’s. You got “Scorpio” by Dennis Coffey and the Detroit Guitar Band. “Shaft in Africa.” “Apache” by Michael Viner’s Incredible Bongo Band. A couple more James Brown songs you can put in there like “Soul Power” and “Sex Machine,” and “Escape-ism,” “Make It Funky” — songs like that.

Teenagers breakdancing next to a wall covered in grafitti, Brooklyn, New York, April 1984.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

When you playing these songs, this is the time for the B-boys to do their thing, to create circles of people around them. People were competing inside that circle; they were doing acrobatics and flips and twists and all kinds of routines, and going down to the floor doing the splits like James Brown, doing footwork, like the best dancers I’ve ever seen. And of course, he was on the microphone with an echo chamber: “Young ladies, don’t hurt nobody-body-body. It’s Kool Herc-Herc-Herc. Herculoids-loids-loids. Going down to the last stop-stop-stop-stop.” It was mystical and magical at the same time. It was disco, but it was ghetto disco.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): It was his playlist that all of the other DJs who aspired to reach his level at the time in the Bronx played. That was Kool Herc’s contribution to hip-hop, his playlist.

WHAT WOULD BECOME known as hip-hop sprang from a foundation of DJs with powerful sound systems who operated around the same time as DJ Kool Herc in the early 1970s. Disco King Mario, who lived one floor above Paradise Gray, who would himself go on to help create X Clan, in the Bronxdale Houses projects, threw some of hip-hop’s earliest jams with his Chuck Chuck City crew. Disco King Mario and Afrika Bambaataa were both members of the Black Spades gang, and Mario lent equipment for some of Bambaataa’s earliest sets.

Afrika Bambaataa, 1980.

David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Pete DJ Jones, a transplant from North Carolina, was popular in Manhattan club circles. He was the first DJ who many, including Kurtis Blow, ever witnessed working two turntables and duplicate copies of the same record, which became the foundation for DJ’ing, extending the breaks of funk and soul songs. Pete DJ Jones also served as a mentor to Grandmaster Flash.

Brooklyn’s Grandmaster Flowers is recognized as one of the earliest pioneers of hip-hop for mixing funk and disco records in sequence and throwing massive block parties. Flowers even opened for James Brown at Yankee Stadium in 1969.

They joined others, like Maboya and DJ Plummer, in laying a blueprint for hip-hop to emerge, but never reaping the attention, adulation, or financial windfall that followed.

Daddy-O (artist, producer, Stetsasonic): I think sometimes people think that the first time that equipment came out and people plugged into the streetlamps, it was hip-hop. That’s not true. The first time you’d seen the sound systems, it was people playing disco: Grandmaster Flowers, my boy Pete DJ Jones. And it was the reggae guys that was playing all the Lone Ranger stuff, the Sly & Robbie stuff, Bob Marley and the Wailers. Those were the first sound systems you saw on the street, disco and reggae sound systems.

Paradise Gray (manager of the Latin Quarter, X Clan): I call my mother the Mother of Hip-Hop, because my first crate of records came from my living room. She was the one that introduced me to George Clinton, James Brown, Maceo [Parker], Bootsy [Collins], Sly and the Family Stone. So, a bunch of the breakbeats. When I finally heard Herc and Flowers and Bam and all of these guys playing the breakbeats, I had a whole bunch of those records already.

DJ Mister Cee (producer): That was the time when a lot of DJs was getting into the craft of DJ’ing and buying them big kickass speakers — and I’m saying “kick-ass” because there used to be a sticker on the speaker that said “Kick Ass.” That was around that time that DJs would play outside and break into a lamppost. Nowadays, there’s an outlet in there. Back then, we would break into the lamppost and splice the wires up and connect to an extension cord. That’s how we would power up.

Paradise Gray (manager of the Latin Quarter, X Clan): Everything about hip-hop was illegal. Do you know how many laws were broken just to do an average street jam? We broke into the light poles. That’s breaking and entering. We cut the wires and we stole the electricity. That’s special services. We didn’t have no permits to do our jams outside in the streets. We just brought our equipment out and we did it. And we dared the police to try to fuck with us.

Sadat X (artist, Brand Nubian): The whole anticipation of seeing the DJ come; you’d see he’d have about two, three dudes carrying record crates. And just to watch them unfold the tables and put the turntables down, and then people start coming and somebody might be making some food. All of a sudden, the music starts. It was like a carnival atmosphere.

DJ Mister Cee (producer): And that all came from Kool Herc from the Bronx and transferred all the way to us in Brooklyn.

Paradise Gray (manager of the Latin Quarter, X Clan): I think that the Bronx narrative of hip-hop is kind of flawed. And when I say it’s flawed, I’ll say that if the meal is hip-hop, maybe the chef was in the Bronx. But the ingredients existed long before the meal.

For me, [Disco King] Mario was the epitome of swag and style and flavor. He was a living, breathing Super Fly–Shaft that lived in your building. He was the well-dressed dude who had charisma, who knew how to dance. And Pete [DJ Jones] had a bar a block from my house. He was a consummate Black businessman in the community. And that seriousness that he brought to DJ’ing and to just being the example of a Black man, was immeasurable in my life.

Kurtis Blow (artist, producer): Once [Kool Herc] started playing that playlist, that’s when he became the father of hip-hop. That’s when he became popular, and all the B-boys started flocking to his club because he played the music that we wanted to hear.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): You went to these jams to get down. And when someone, another opponent, got in the circle with you, if you were a B-boy or B-girl, then it was your intent to burn them. Burning was basically like beating them in a dance battle. And so, B-boy culture was nomadic. Anywhere B-boys and B-girls knew that a DJ was going to be playing the beats, that’s where they went. And that was exclusive to the Bronx from about 1973 till about 1978.

Grandmaster Caz (Cold Crush Brothers): By the time I saw Herc, I was about 15. Seeing his sound system and seeing his party for the first time just totally blew me away. And when I first saw him in the club, that pretty much was the selling point for me as far as getting involved in hip-hop.

DJ Charlie Chase (Cold Crush Brothers): The first party I had attended with Herc, he was rocking. He had a big set and that’s what intrigued me, the size of his set. And he had Clark Kent [of the Herculoids] playing with him. And they were making announcements on the mic.

Kurtis Blow (artist, producer): He was the man on the microphone, Coke La Rock. He was more like a street dude, a street hustler. So he had the gift of gab, and he used to talk a lot of smack. Herc was from Jamaica. He’s just getting to the Bronx and he meets Coke La Rock, and Coke La Rock has all the lingo. So they became friends and partners.

Michael Holman (journalist): So, you’ve got DJs experimenting like Herc, like Bambaataa, like Grandmaster Flash, like Jazzy Jay, who are throwing parties in the park at night. In the Bronx River projects, you’ve got Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation, who reign supreme. In other neighborhoods, like near Sedgwick Avenue, you’ve got Kool Herc, and they all decide, “Well, since [Patti] LaBelle is playing downtown tonight and everybody’s going to be going down there, I’m going to have a party at the same time, and all the kids who can’t go downtown are going to come to my party in the park.”

And people are partying and dancing to the DJs spinning records, and he’s playing all these disco hits for these middle-school kids who can’t go downtown for a myriad of reasons, and he has this automatic audience. But he is not being hired by a club downtown and isn’t being told what to play and what not to play. He can play what the fuck he wants to play, because it’s his party. No one’s paying him to do this. It’s for fun. It’s for love.

So, now they’re not tied into only playing disco records, he’s throwing in great dance hits like James Brown from 10 years before. Oftentimes they would throw down some Caribbean or Jamaican hits, dub hits. Then crazy, wild people like Bambaataa, who was considered “King of Records,” would even throw in records that had no business being played at a Black-and-Brown uptown, urban party, but because there was an element in the song that was so funky you couldn’t deny it, he would throw it on, like the TV theme song of I Dream of Jeannie, or the Monkees’ “Mary, Mary.”

THE ELEMENTS THAT created hip-hop rose through surrounding blight and institutional neglect in the South Bronx. The costly Cross Bronx Expressway, the vision of urban planner Robert Moses, wrought immense havoc and heartache. Completed in 1963 after 15 years of construction, the first expressway built through an urban area bifurcated the Bronx, decimating and displacing mostly African American and Puerto Rican communities. Many of the residents who remained in the area relocated to massive public housing projects.

The South Bronx’s economy collapsed. Real estate values plummeted. Fires ravaged the area as arson became prevalent. Burned-out, gutted, and abandoned buildings constituted entire blocks. Drug consumption increased. The exodus in population resulted in the reduction of public programs. In October 1975, President Gerald R. Ford decided against offering federal assistance to New York, prompting the New York Daily News to run the infamous front-page headline: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Throughout the 1960s, gangs like the Black Spades, Ghetto Brothers, Savage Skulls, and Seven Immortals rose to prominence as the decay in the South Bronx surged. They were comprised mostly of young Blacks and Latinos in search of community and protection. In December 1971, several gangs reached a truce at the Hoe Avenue Peace Meeting, following the murder of Cornell “Black Benjy” Benja- min, a member of the Ghetto Brothers who had tried defusing a fight between two gangs. The truce is regarded by many as a vital component of hip-hop’s formation. Some leaders of gangs threw block parties as a means to build community and fellowship. While long-standing peace remained elusive, gang members were encouraged to not use violence against one another. Soon, some crews instead engaged in B-boy battles.

Lady B (artist, radio DJ, Philadelphia): It was a terrible time for the Black community. We were gang-stricken, pretty much like it is now, unfortunately. But hip-hop saved lives. We stop fighting with guns and knives and start battling with microphones and turntables.

Paradise Gray (manager of the Latin Quarter, X Clan): When I was a kid and Disco King Mario brought his equipment out and DJ’d in the Bronxdale projects, everybody would come together and cook they food, and drink they beer, listen to the music, dance with the girls. And if you messed up the block party, or you messed up a jam, the gangsters will beat the shit out of you.

The gangs were a part of hip-hop from day one. You had to regulate. If you didn’t have that kind of street credibility and juice, you couldn’t come out with your equipment, because you wouldn’t go home with your equipment.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): Most of the crews that represented each block were ex–gang members. And so the gang element was still very, very present even though the gangs started to diminish — all they did was, instead of calling themselves a gang, they called themselves a crew. But most of them still behaved the way that a gang behaves.

Like for example, our security, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s security, was called the Casanovas. And the Casanovas were all ex–Black Spades members. Just like the Zulu Nation that secured Bambaataa. Most of those guys were ex–Black Spades.

BORN LANCE TAYLOR, Afrika Bambaataa was a former member of the Black Spades gang who assembled the components of the brewing culture — DJ’ing, MC’ing, graffiti, and B-boying — and united them within a singular community.

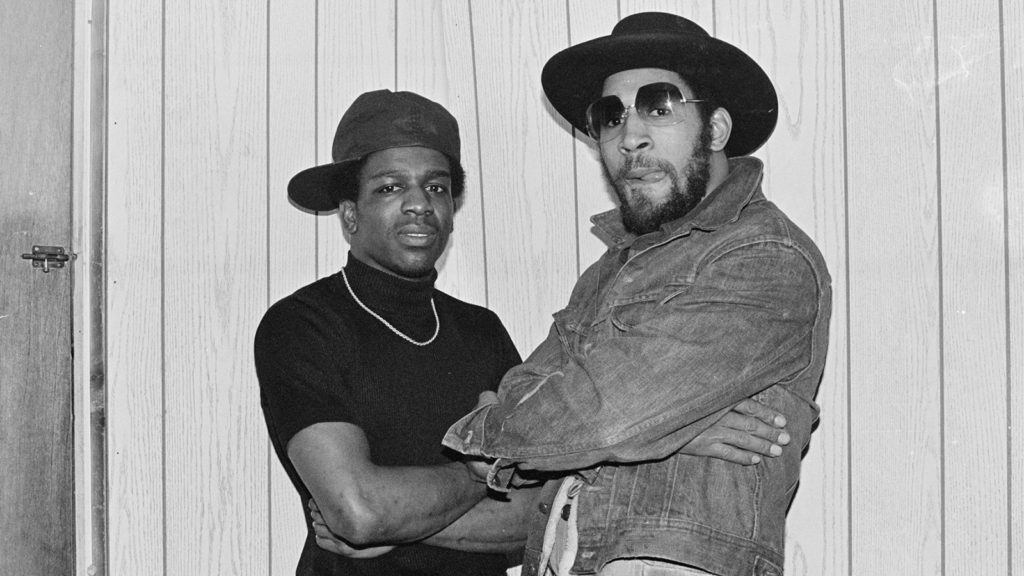

Grandmaster Flash, DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Chuck D attend Columbia University’s Rap Summit circa November 1993 in New York City.

Kevin Mazur/WireImage

Bambaataa grew up in Soundview’s Bronx River Houses and gained inspiration from the indivisibility of the Zulu people of South Africa. Under Bambaataa, former gang members became DJs, MCs, B-boys, B-girls, and graffiti artists within his Zulu Nation. Bambaataa performed at the Bronx River Community Center and at block parties throughout the East Bronx in the mid-to-late 1970s. He developed a reputation as the “Master of Records” by compiling a vast and diverse collection, playing everything from hard rock to funk to classical music. Like Kool Herc, he kept the source of his breakbeats hidden by blacking out the names of records. A number of pioneering DJs and two notable crews of artists — the Jazzy Five (Master Ice, Mr. Freeze, Master Bee, Master Dee, and AJ Les) and the Soulsonic Force (Mr. Biggs, Pow Wow, and G.L.O.B.E.) — surfaced from the early days of the Zulu Nation.

MC Shy D (artist, producer): Those was fun days for me, because I was young; and Bambaataa, he used to get the speaker in the window, in the projects; and everybody gathered round the building and we just had good times out there.

Afrika Islam (DJ, Zulu Nation): The record part came in so heavy. [Grandmaster] Flash or [Grand Wizzard] Theodore, they might have 10 crates of records, but if we came in at 42 or 50, we never had to repeat a record. We would just continuously come in and bang you in your head.

Afrika Islam (DJ, Zulu Nation): To call yourself a DJ at that time then, you needed vinyl. At that age, 13, 14, you got to remember this is all new. There were no limits at this stage. So everything we did was creatively new, each and every single time. And you adjusted every single week: that worked, this didn’t work.

Aaron Fuchs (president, Tuff City Records): Bambaataa letting me see his record collection … [DJ] Red Alert just told me a couple of months ago that that was very rare. It was like being given the Coca-Cola formula.

What it was, was this unprecedented mix of island music along with American Black music and a range of other more segregated American Black music, like go-go, little bits of Haitian music, salsa. I knew right then and there I was privy to something important.

GRANDMASTER FLASH, BORN Joseph Saddler, evolved the craft that Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa had started by inserting finesse and technique into DJ’ing. He moved to the South Bronx from Barbados with his family in the 1960s. He studied his father’s extensive (and forbidden) record collection, and learned how electronics worked by taking them apart and reassembling them. He studied DJ Kool Herc, trying to figure out his method for maintaining the beat, and in the 1970s Grandmaster Flash became a DJ’ing partner with DJ Mean Gene Livingston, who advanced to form the L Brothers.

Photo of Grandmaster Flash, 1980s.

David Corio/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Among Grandmaster Flash’s many contributions was his “quick mix” theory, a discovery that served as a backbone for hip-hop music. He found that by using two copies of the same record he could play the breakbeat on one, while searching for the break on the second with his mixer and syncing it to play as soon as the first had finished. He had transformed his turntables into a musical instrument and eventually marked the breaks on the records by hand.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): Between 1976 and ’77, a DJ named Grandmaster Flash created this technique on the turntables. It changed everything.

Right before Grandmaster Flash became notable, there was a time period in which aspiring DJs didn’t have two turntables and a mixer, because that was pretty expensive at the time.

Afrika Islam (DJ, Zulu Nation): How many 16-year-olds are going to come up with [the money for] a fully made sound system?

Kurtis Blow (artist, producer): B-boying was the main thing about a Kool Herc party. A Flash party was more about Flash and you standing out in front of a stage watching Flash on those turntables cut it up.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): The contrasting difference between going to a Kool Herc party and going to the Grandmaster Flash party was that [Kool Herc] didn’t cut the records back and forth. He just placed the needle on the record and let the records play, and B-boys and B-girls would go off whenever the breakbeats did play.

Grandmaster Flash would only play what he deemed the dope part of the beat, which was the break. And so, as a result of that, and as a result of his ability to catch the beat back and forth from turntable to turntable, there was never a lull in the activity or the excitement, because he was constantly cutting and scratching records.

Bill Stephney (Bomb Squad, Def Jam): The way hip-hop happened in that late-’70s period, it was relatively sudden and so distinct from anything else that was going on with the use of the turntables and the extended beats. It relates to the language and the dress and the diversity, too, of the Bronx, especially of having Blacks and Latinos and even a handful of white kids too, all going to parties and not even thinking twice about it, when there were gang wars a year or two before. All of it just crystallizes.

DMC (artist, Run-DMC): If you listen to early rap, everybody would use disco. People’s minds is blown away how connected disco’s presentation was, just a hybrid form or cousin of hip-hop. But people forget the Fat Boys was called the Disco 3 when they first came out. So it was all disco, because it was about the records and the music.

Kool Moe Dee (artist, Treacherous Three): Being eight and nine while it’s happening, you’re aware of it, but you’re not really able to participate in it. So, by the time I’m 14, I get to hear Lovebug Starski, not only at a block party, but I heard him at a place they called the Renaissance in New York. He was the first, in my opinion, the first DJ/MC, because the DJ had a mic, that would do a combination of the hip-hop breakbeat stuff and the R&B.

AS THE PROGRAM director of WBLS-FM, legendary DJ Frankie Crocker maintained a sizable influence over popular music and, perhaps, an unwitting one in hip-hop’s evolution and growth. Crocker was already known in New York City by the time he arrived at WBLS in the early 1970s. He propelled the station’s ratings by introducing the urban contemporary format and playing a wide range of selections, including disco, R&B, and hip-hop music. On air, Crocker defined the charismatic master of ceremonies, delivering imitable rhymes that provided a blueprint for future artists and signing off each night to “Moody’s Mood for Love.”

Though wary of a changing of the guard, Crocker did not deny hip-hop music’s popularity. He broke some of the earliest hip-hop records and hired Mr. Magic, hip-hop’s groundbreaking radio DJ, to WBLS.

Run DMC on the December 4th, 1986 issue of Rolling Stone.

Moshe Brakha

DJ Mister Cee (producer): If you wanted to get on the radio and you lived in New York City in the late ’70s and the ’80s, then Frankie Crocker was one of your idols.

Bill Stephney (Bomb Squad, Def Jam): He’s not probably hip-hop as we define it today, but there was a point when the culture itself was sort of like the Mafia. La Cosa Nostra, I think that the English translation is “This thing of ours,” and that’s sort of what hip-hop was as it was developing from the Bronx and from Harlem and through the New York area. It was a DJ-driven party culture. And whether you’re DJ Hollywood as an MC or even the other rappers, MCs who came up, they’re all influenced in terms of tone, phrasing, attitude by Frankie Crocker. The literal term MC, master of ceremony, that’s really based on what Frankie Crocker did either on the radio or at parties or at concerts.

DJ Mister Cee (producer): First and foremost, with Frankie Crocker, his voice was very distinctive. At that time, it was just true New York radio. It wasn’t called Black radio; it was just radio. So, you would hear Michael Jackson, then you would hear a Madonna record, and then you would hear Prince, and then you would hear Hall & Oates. It wasn’t pigeonholed. Whatever the Black community liked, whether the artist was white or wherever they came from, Frankie Crocker was playing the record. That was a big, big deal as well, which is why so many white artists from that era got appreciated by Black people, the Madonnas and the Tears for Fears and the Hall & Oates.

Jeff Sledge (A&R, Jive Records): He was the program director, so he played what he felt. He would go out to a club the night before and hear this new girl, Madonna, who’s got this song called “Holiday.” He would play it that next day. Like, “Yo, I heard this record in the club. This shit’s hot.” He was playing test pressings and he was playing records that aren’t even affiliated with just major labels. He’s just playing the hot shit.

Bill Stephney (Bomb Squad, Def Jam): In many respects, I don’t know if hip-hop happens in New York without Frankie Crocker and without the variety of music that Frankie Crocker, as a Black program director, played in devising the most varied music format that any radio station had offered anywhere. Here was a guy who could play “I Got My Mind Made Up” by Instant Funk, into “Stars in Your Eyes” by Herbie Hancock, into “New York, New York” by Frank Sinatra, and 15-year-old Black kids in Brooklyn would be into it.

And the parties that we attended in the late ’70s, early ’80s, in the area, reflected that variety. Bam and Herc and Flash and Spectrum City, Pete DJ Jones, King Charles, the Disco Twins, and Infinity — all these folks who were DJ’ing, generally reflected the nuanced diverse playlist of what Frankie did. You couldn’t hear that anywhere else.

NEW YORK CITY teetered on the brink in the summer of 1977. Economic stagnation and soaring unemployment crippled the city. The serial killer known as the Son of Sam stalked victims, while a sweltering heat wave pummeled the five boroughs.

On the evening of July 13, successive lightning strikes strained the area’s overburdened power grid and plunged most of the city into pitch-blackness. Confusion and chaos quickly ensued. People took to neighborhood streets and some ransacked stores.

The lights remained off for more than a day. In that time, more than 1,500 businesses had been vandalized. Consolidated Edison, the city’s power provider, labeled the outage as an “an act of God.” A congressional study estimated that the damages and losses totaled more than $300 million.

Daily News front page July 14, 1977, Headlines: BLACKOUT! Lightning Hits Con Ed System – 1977 Blackout Power Failure

NY Daily News via Getty Images

While most sought food and domestic necessities, some trained their attention on electronics stores, breaking down doors and snatching equipment. For them, the darkness provided an opportunity to finally build their own audio system or reap the profits from secondhand sales. Overnight and under darkness, new DJs started populating the area. Crews formed after mixing and matching newly gained equipment to form a cohesive system.

Some dismiss the notion that the blackout provided a catalyst for hip-hop’s uprising, that the ingredients for the genre were already in circulation and simmering, and the hypothesis of lightning bolts helping to spark the genre is too tidy a narrative. Others who lived in New York City at the time of the blackout insist that the event helped jump-start the early scene.

DJ Charlie Chase (Cold Crush Brothers): The night before [the blackout in] ’77, I was in a band and we had a gig in Brooklyn. The next day, I was so exhausted, I did something that I never did in my life, and that was go home early. I was home and I was laying in bed and I remember just nodding out and watching television, and all of a sudden: poof.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): I’m in the backyard of the housing complex I grew up in, playing basketball and the streetlights were just coming on, and I went up for a jump shot, and just as it was going in the basket, one by one, the lights began to go out. We didn’t think anything of it at the time, and then we looked up and no lights in any building for as far as the eye could see were on.

Easy A.D. (Cold Crush Brothers): Everybody froze for a second, and they was like, “Blackout.”

MC Debbie D (artist, South Bronx): And then people start opening up the fire hydrant, because it’s hot. The reason for the blackout is because it was an 11-day heat wave. By the time you get to this 11th day, the electricity is so overused in New York City that that’s what caused the blackout.

DJ Mister Cee (producer): Right in front of my building in my projects [in Brooklyn], we cracked open that fire hydrant. All we did that whole day was, we just had water fights. Throwing water on each other that whole day. We had a blast in my projects.

Easy A.D. (Cold Crush Brothers): Immediately, people started pulling gates up and going into the store. I can honestly say to you that I was immensely afraid of my mom, because if you brought something home that wasn’t yours, it was a major problem. So I didn’t go into the store.

Grandmaster Caz (Cold Crush Brothers): The blackout was scary as hell. We were DJ’ing with another crew at the park, and all of a sudden the lights started going out and we thought that we had blew out the power, because we were attached to the light pole. But not only did the set go out, the entire block went out, and the whole Bronx went out. It was pandemonium after that. It was like everybody realized at the same time, “Oh, shit. Blackout. Run for the stores.” And everybody just fanned out, all different directions, toward stores.

Merchant after the 1977 blackout power failure in NYC.

Keith Torrie/NY Daily News/Getty Images

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): We walked to the neighborhood supermarket and looked in the window; we didn’t see any employees and the lights were off. So, we picked up a big steel trash can and threw it through the plate-glass window, and we all just went in. And it was about maybe 30 of us. We got a sledgehammer and we beat the safe until we unhinged it from the ground. And we walked with the safe up to this tenement building, and took the safe in the basement; and a few OGs [original gangsters] that was down with one of the gangs called the Peacemakers broke the safe open, and they divided up the money and the food stamps. I was 14 and they gave me, from what I remember, $1,600 in food stamps and about $1,200 in cash. That was my cut.

And so I took the money, the food stamps home, gave my mom some, stashed the rest in my air-conditioner duct, and then went to this store called Sneaker King because I heard that that store had gotten looted but that if I hurried up I could get myself some free sneakers. When I got to Sneaker King, I walked in there and came out with two tall kitchen trash bags filled with boxes of sneakers all my size.

Muhammad Islam (security manager, A Tribe Called Quest): We was poverty like crazy in the hood. You seen an opportunity to take some pants, some TVs, whatever the case may be, it happened.

DJ Charlie Chase (Cold Crush Brothers): GLI is a company [that sells] audio equipment. At the time, they were a very popular company. They had a GLI store on the Concourse, right down the block from my house. And they got hit hard. They smashed the glass, and they took everything. They had some crazy, crazy, crazy equipment in the windows, and that store was completely cleaned out. That’s one of the places Caz told me he made a stop at that night.

Grandmaster Caz (Cold Crush Brothers): I didn’t get a whole lot of stuff, because I was there trying to protect my own equipment that was in the street, but I did run around the corner to the place I got my first DJ set from. I ran right around the corner to that place, helped pull the gate down, kicked the glass down and everything, and pulled me a mixer out of there.

DJ Charlie Chase (Cold Crush Brothers): A lot of motherfuckers had GLI speakers now.

DJ Clark Kent* (producer): That’s when I got my first set of turntables. I was this young boy who was deep with learning how to DJ, and I never had my own set. I just wanted to be equipped. I just wanted my own turntables. If I was smart enough back then I would have thought, “Yeah, you’re gonna need an amplifier and some speakers, too.” But it was just me and my cousin, we couldn’t take all that.

* A different Clark Kent performed with DJ Kool Herc and the Herculoids.

MC Shy D (artist, producer): They was tearing them stores up. Bambaataa had the main equipment in Bronx River, the big stuff, but you had guys 15, 16, they started coming out with their little mini sets. Bambaataa influenced everybody, but that blackout, everybody went crazy, man. People got equipment and everything.

DJ Clark Kent (producer): It definitely helped me. I definitely got a turntable and a mixer out of the situation. I’m from an impoverished neighborhood, and we did whatever we could to do, whatever we wanted to do. Life in the hood.

MC Debbie D (artist, South Bronx): How else were you going to get it?

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): We used to have after-school programs that we could count on and go play ball and get extra support with your schoolwork. But the federal funding for those programs were all cut. And as a result, most of the kids were left to the streets. So that’s why the gang violence became so prevalent. But then, hip-hop gave people options.

In 1977, the blackout is what changed the scope of things, and it really gave the majority of kids who would have probably been victimized or involved in gang violence in some way, it gave them an option. Gang violence began to diminish because being involved in hip-hop culture, it gave latchkey kids something. Their parents weren’t home when they got home from school; eventually they’re going to be out in the street with no supervision, left to their own devices.

Paradise Gray (manager of the Latin Quarter, X Clan): Before the blackout, people in the Bronx had horrible sound systems. Queens and Brooklyn had the full banging systems at the beginning. But not too many people in the Bronx could afford big sound systems until after the blackout. Then, everybody had sound.

Rahiem (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five): The blackout of 1977 is what helped to spawn a multitude of aspiring hip-hop practitioners, because prior to that, the majority of aspiring DJs didn’t have two turntables and a mixer or the speakers. So, when the blackout happened, it just seems that everybody got the same idea at the same time. And when the lights came back on in New York City, everybody had DJ equipment.

MC Debbie D (artist, South Bronx): When you get to the blackout, it shifts hip-hop. It’s a pivotal moment, because like a week later, everybody was a DJ. Everybody.

Easy A.D. (Cold Crush Brothers): We needed something to change the way that we felt. We didn’t call it hip-hop at the time, but the music and the rhyming and the creative mind came out. So out of something that would be unattractive came something elegant and phenomenal and groundbreaking.

At every level that you can imagine, it turned the world upside-down. The Bronx went from being decayed into something beautiful. The vibration of the music and the combination of bringing all those elements together, you had to be in there to feel it, because most of the time people only experience the music. But when you have all those elements in one place together, then you understand the essence of the hip-hop culture.

Afrika Islam (DJ, Zulu Nation): We made lemonade from lemons.

I guess we partied from the soul, that’s the only word that I can really put it. We partied from the soul and enjoyed music because it was free.

Excerpted from the book “THE COME UP: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop” by Jonathan Abrams. Copyright © 2022 by Jonathan Abrams. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

[ad_2]

Source link