[ad_1]

This story was originally published in Flatwater Free Press.

Kearney – Kearney’s 11-acre property contains dozens of what appear to be shipping containers.

Inside the metal box are racks and computer racks. Thousands of them solve complex math equations around the clock.

Here on the outskirts of town, between sun fields and cornfields, thousands of computers mine cryptocurrency.

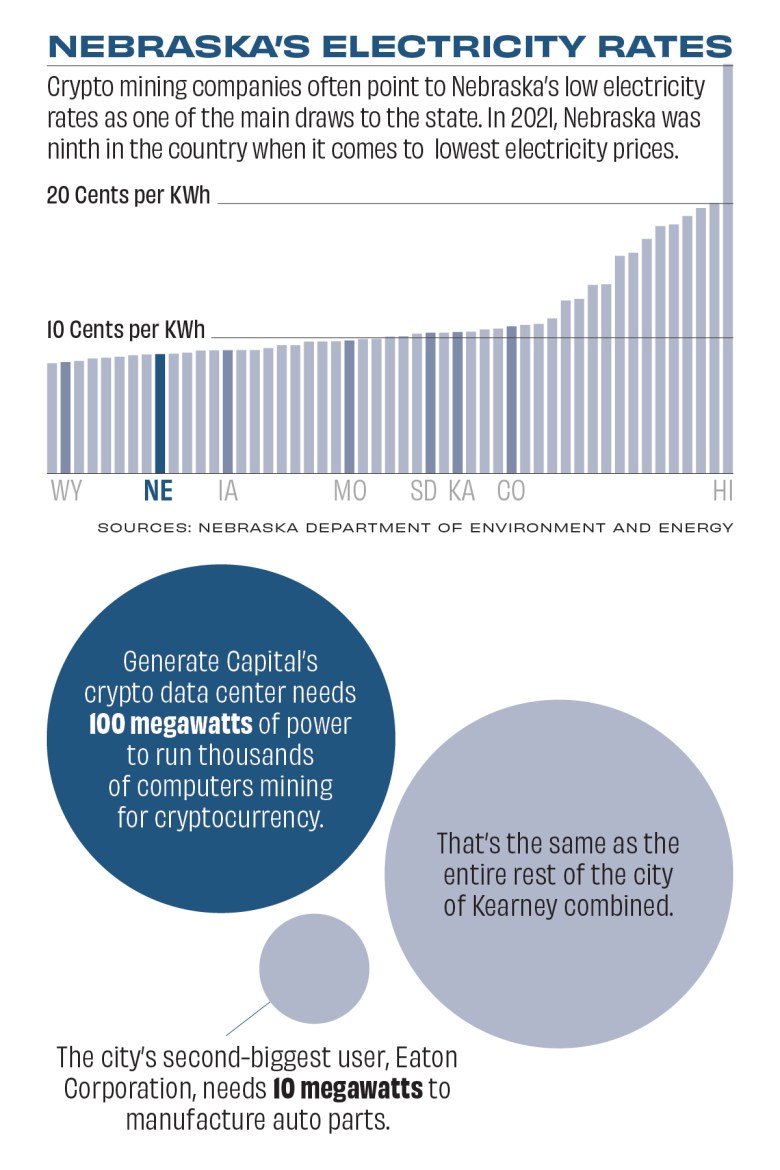

Together, they consume as much electricity as the entire city of Kearny. 33,790, do it.

It is one of the largest cryptocurrency data centers in Nebraska and is a host site for computers that compete to validate crypto transactions and add them to digital currency.

It may also be the first of many such centers to set up shop in the state, as the still-new and volatile crypto industry is carving out a home in rural America.

Crypto instability is already hitting Kearney strongholds. In September, his data center company Compute North declared bankruptcy. Kearney’s estate was sold to one of his company lenders, Generate Capital.

But even the plummeting crypto prices, the infamous failure of crypto exchange FTX, and the arrest of co-founder Sam Bankman-Fried haven’t stopped the industry from expanding in Nebraska.

Just last week, Hall County commissioners approved the construction of a 14-megawatt encrypted data center near Grand Island.

“We weren’t actively pursuing these, but they came to us,” said one of the many utility districts in Nebraska that has handled crypto company calls in recent years. Neil Niedfeld, chief executive officer of the Southern Public Power District, said.

Crypto, a digital currency, relies on a network of computers to maintain a blockchain. Think of it like a digital ledger of transactions. Computers solve complex math problems to validate transactions and add them to the ledger. In exchange, they receive digital “coins” such as Bitcoin and Ethereum along the way.

Currencies are mostly unregulated and not tied to banks. Like the US dollar and British pound, it is not backed by any government. For crypto enthusiasts, the decentralized structure is part of the appeal.

Gus Hurwitz, a law professor at the University of Nebraska School of Law, said: “Fundamentally, the cryptocurrency business is about converting electricity into computer computation.

Companies like Kearney’s Compute North act as rental spaces for computers that run everything. Crypto miners pay for space, maintenance, internet, and all-important electricity to ship their equipment.

With computers running virtually 24/7 and fans running to keep them cool, the main cost of doing business is electricity. The companies that operate these hubs need electricity. They are looking for it cheap.

About five years ago Compute North found it in Nebraska. Nebraska is the only state that is completely powered by a public utility company that is obligated to provide the cheapest electricity possible.

NPPD Economic Development Manager Nicole Sedlacek said: “Eventually, they got to calling us.”

The company had several other standards. They liked the combination of carbon-free energy in the power district. They needed affordable land. They looked for a place that could handle the enormous power load and a local government that was open to the idea that cryptocurrency was coming to town.

Kearney had everything they were looking for.

A town in central Nebraska was already trying to develop a technology park. The company was vying for his Facebook data center, but lost a tender in Altoona, Iowa about a decade ago.

Encrypted data centers promised jobs, but not in a way that squeezed housing or took workers away from employers already in town. 20 years as mayor.

Clouse is also an account manager for NPPD. He asked about energy needs in his first meeting with Compute North. What the mayor heard excited him, he said.

NPPD had enough electrical capacity to handle the data center and didn’t need to generate extra power for Compute North. The data center doubles the power capacity of Kearney’s grid, making power more stable and cheaper. It would also mean an influx of cash.

“More cargo means more revenue, which goes into Kearny’s general fund,” says Clouse. “That’s over $1 million a year for Kearney. For a community of our size, that’s pretty significant.”

But for some, Kearney’s data center, and others soon to be up and running in Grand Island and York, shouldn’t be celebrated.

“It’s not about job creation or opportunities in Nebraska,” said Scott Scholz, spokesman for the newly formed advocacy group Nebraskans for Social Good. “This means businesses outside the state are using our electrical system to their advantage.”

With the exception of Clouse, who abstained because of its utility role, the Kearney City Council unanimously decided in June 2019 to approve a development agreement with Compute North.

The company received 11 acres (worth $165,000) of free land, paid for by the Buffalo County Economic Development Council. The city gave the company a power rebate, capping him at $1.1 million. The company hit that cap in August.

Nebraska Public Power added a mobile substation to handle the increased load. Utility District is working on his new $12.5 million permanent substation that will send energy exclusively to cryptocurrency mining locations.

In return, Compute North has committed to hiring and has hired 11 people. This assisted in the development and addition of electrical capacity at Kearney’s Tech Park. By 2021, we have grown to 100 megawatt customers.

By comparison, city-wide energy demand peaks at 100 megawatts. Kearney’s second largest user is manufacturing company Eaton, with the largest he reaches 10 megawatts, Clouse said.

Pat Hanrahan, NPPD’s general manager of retail services, says the load on the data center is very high and constant. And it’s flexible. For example, if the NPPD needs more power from the grid to heat your home in the cold winter, your data center could easily go haywire.

But the sheer amount of electricity used raises environmental concerns, Scholz said.

A year of global mining of cryptocurrencies would use more electricity than the country of Argentina, according to estimates in the White House report on cryptocurrencies and climate change. This corresponds to almost 1% of the world’s annual electricity usage.

In New York, lawmakers recently passed a bill banning fossil fuel-based cryptocurrency mining projects for two years. In Montana, coal-fired power plants were shut down to support environmentalists until a cryptocurrency data center opened nearby.

NPPD in Nebraska already had the energy capacity to power the Kearney data center, Hanrahan said. Utilities didn’t have to build new power generation to supply it.

About 62% of NPPD’s energy generation is carbon-free, a number that has remained stable before and after Compute North came to Kearney, said NPPD spokesperson Grant Otten.

Still, Bruce Dvorak, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, said a data center’s constant energy usage is likely to be drawn from all available energy sources.

“It comes from a mix of greener sources such as wind and less green sources such as coal and natural gas,” Dvorak said.

The NPPD’s economic development department has responded to calls from about 25 different cryptocurrency companies interested in Nebraska over the past five years, according to Sedlasek. With China banning cryptocurrencies in 2021, the calls have increased.

Some towns, like Kearney, were open to the idea, Sedlacek said. Others are more hesitant. They welcomed economic development.

“But we don’t want cryptocurrencies,” they told her.

The cryptocurrency market is young, unfamiliar to the general public, and highly speculative and volatile. Bitcoin price peaked at $68,764 in November 2021. Since then, it has plummeted 75% to $16,625 in January.

In November, cryptocurrency exchange FTX filed for bankruptcy, shocking an industry already in crisis. FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried was subsequently arrested on multiple fraud charges, fueling distrust among crypto skeptics.

“We’re definitely at the bottom of the industry,” law professor Hurwitz said. We need to leverage our capital.”

Compute North, which opened a data center in Kearney, declared bankruptcy late last year, citing rising energy costs and falling profits as the value of bitcoin plummeted. did not do it. Today, clusters of computers between cornfields and solar power plants continue to validate transactions and mine new cryptocurrencies.

NPPD Economic Development Manager Sedlacek said: “We as a utility have spent a lot of time really talking about it.

She thought calls would slow down last year when digital currencies collapsed. But companies kept calling.

Several other projects are currently underway in Nebraska.

York City Council decided in April to sell the land to Omaha company BginUSA, which wants to build an $8 million mining facility. In Minden, Compute North’s planned expansion is in the process of being transferred to New York-based Foundry Digital.

In November, a group of residents opposed to a proposed cryptocurrency data center near Doniphan met at a Hall County Commission hearing.

“This is not a farm facility,” resident Justin Gregg said in a public comment, according to NTV News. Yes, and it should stay that way.”

Interested companies withdrew their conditional license requests before the commissioner voted.

This week, Hall County approved a conditional use permit for another cryptocurrency project near Grand Island.

Questions have been raised about the future of cryptocurrencies, including regulation and possible market prices. Last year, the Biden administration released recommendations for future U.S. regulation.

Hurwitz said Nebraska towns and utility districts want to fully understand the risks cryptocurrency companies can face.

“Whoever wants to contribute money – companies, municipalities, investors, bankers, lenders – will do so more risk-conscious,” he said. “I’m not going to take credit for anything.”

With the future of cryptocurrencies uncertain, Sedlacek asks the companies calling NPPD. What do you think this will look like in the future? And what will happen when crypto is gone?

Many have told her that she may eventually divert her massive computer power to other industries such as banking, finance and healthcare.

“They really say cryptocurrency is the first step into this advanced computing space,” said Sedlacek.

flat water free press Nebraska’s first independent, non-profit newsroom focused on critical research and feature stories.

flat water free pressSeacrest Greater Nebraska reporters cover issues throughout the state of Nebraska. Named after philanthropist Rhonda Seacrest and her late husband James. James is proud that he has led Nebraska newspapers through his publishing of Westerns for 40 years.

[ad_2]

Source link