[ad_1]

In 1938, los angeles times Writer Madin Malone describes a trend he’s noticed on the streets of big cities on the West Coast: [sic] A few years ahead of style, well-dressed Americans will be wearing what they’re wearing now on Los Angeles and Main Street in a few seasons. ”

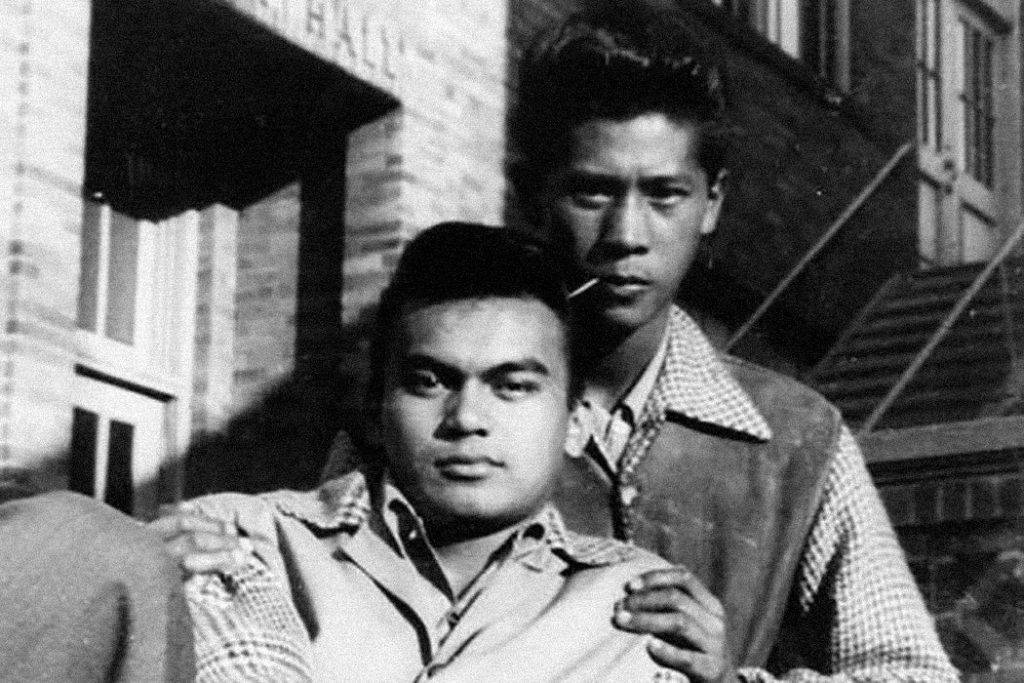

Malone wasn’t the only one to think so. As American studies scholar Dennis Cole writes, in the 1930s and his 1940s, Filipinos, including those who spent their days working the farms, were widely known for their keen sense of style.

In the late 1920s, the federal government made it increasingly difficult for Asians to immigrate. As a US territory, the Philippines was exempt from these restrictions until 1934. Island youth flocked to America’s Pacific coast to fill labor gaps in the agriculture, lumber, and canning industries. Many people bought cars on credit, allowing them to move from one remote job to the next and allowing access to the city center.

It was in these cities that Filipino workers gathered to find communities and go to the movies. Many of these immigrants grew up watching white American culture on the big screen, and movie theaters remain a big draw in West Coast urban areas, Khor said. However, they often encountered discrimination there. Some theaters posted signs banning Filipinos outright, but confining them to a separate section. Furthermore, the Japanese-owned ones were specifically catered to the Filipino audience.

Inspired by Hollywood actors, many Filipino immigrants bought expensive custom Mackintosh suits. Filipino owned tailor shops popped up and sold them. And in between hard labor, many of these well-dressed men frequented dance halls. In 1929, at the Northern Monterey Chamber of Commerce, Judge DW Rohrback allowed Filipino men to “swagger like peacocks and attract the eyes of young American and Mexican girls”. complained.

In 1929 and 1930, white Californians launched violent anti-Philippine campaigns. In one instance, hundreds of white residents of Watsonville, California formed a mob and attacked a Filipino man in the city and on a local ranch. According to Coe, unlike attacks on Chinese and Japanese immigrants, who were often seen as isolated and terrifyingly alien, racism against Filipinos is often seen as a sign that they are Americans. Like the white Californians who targeted Mexican-American immigrants in the later Zoot Suit riots, Filipino attackers used fashion and style as a pretext for action. .

“Filipinos got into trouble in Watsonville because they wore ‘shyker’ clothes, danced well, and spent more money than their fellow farm hands in the Nordies,” he said. , one of the contributors to the Federal Writers Project wrote at the time.

But the Filipino persisted and kept going to the movies. By the 1940s, many theaters had midnight special screenings of Filipino films.

“In the segregated midnight dimmed theater, Filipino audiences were able to enjoy these projections of the motherland’s imagination without public condemnation,” wrote Coe. I was able to enjoy my time in the dark.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join Patreon’s new membership program today.

means

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers and students. JSTOR Daily readers have free access to the original research behind the articles on JSTOR.

Posted By: Denise Coe

Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 81, No.3 (August 2012), pp.371-403

University of California Press

[ad_2]

Source link